Convex Functions

Contents

9.8. Convex Functions#

Throughout this section, we assume that

We suggest the readers to review the notions of graph, epigraph, sublevel sets of real valued functions in Real Valued Functions. Also pay attention to the notion of extended real valued functions, their effective domains, graphs and level sets.

9.8.1. Convexity of a Function#

Definition 9.43 (Convex function)

Let

An extended valued function

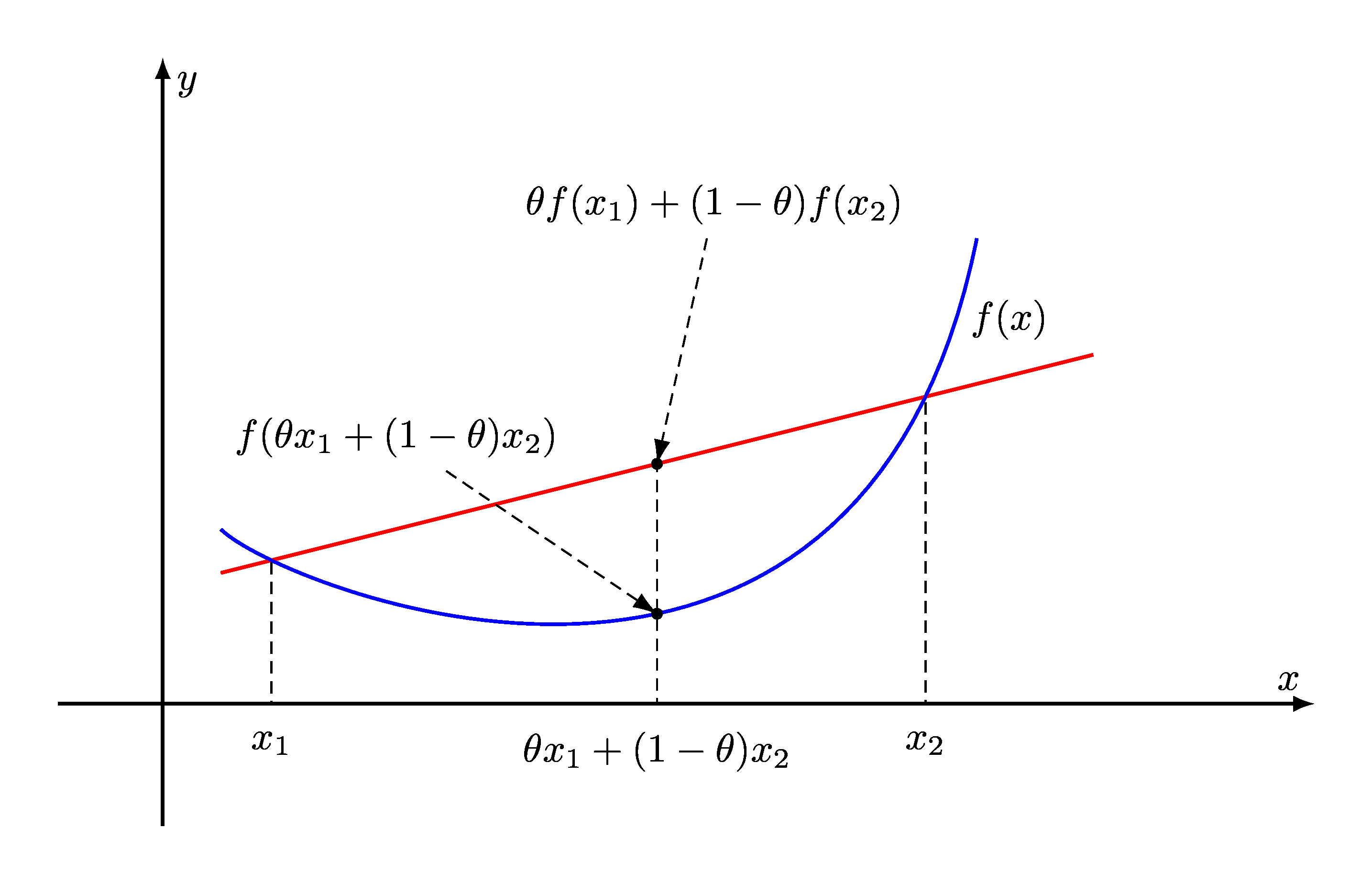

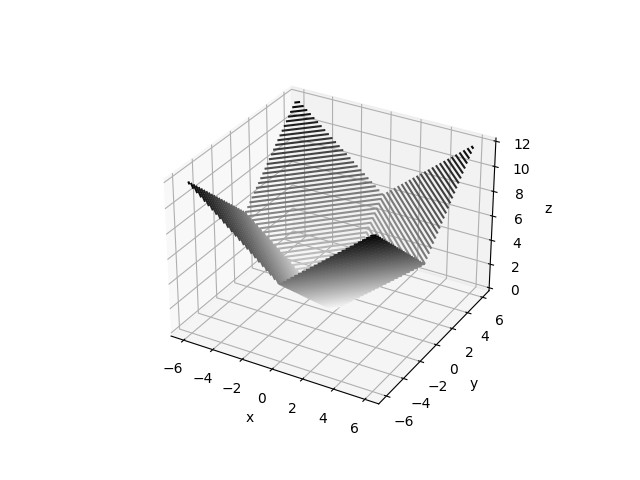

Fig. 9.3 Graph of a convex function. The line segment between any two points on the graph lies above the graph.#

For a convex function, every chord lies above the graph of the function.

9.8.1.1. Strictly Convex Functions#

Definition 9.44 (Strictly convex function)

Let

In other words, the inequality is a strict inequality

whenever the point

9.8.1.2. Concave Functions#

Definition 9.45 (Concave function)

We say that a function

Example 9.25 (Linear functional)

A linear functional on

i.e. the inner product of

Theorem 9.67

All linear functionals on a real vector space are convex as well as concave.

Proof. For any

Thus,

9.8.1.3. Arithmetic Mean#

Example 9.26 (Arithmetic mean is convex and concave)

Let

Arithmetic mean is a linear function. In fact

for all

Thus, for

Thus, arithmetic mean is both convex and concave.

9.8.1.4. Affine Function#

Example 9.27 (Affine functional)

An affine functional is a special type of

affine function

which maps a vector from

On real vector spaces, an affine functional on

i.e. the inner product of

Theorem 9.68

All affine functionals on a real vector space are convex as well as concave.

Proof. A simple way to show this is to recall that for any

affine function

holds true for any

In the particular case of real affine functionals,

for any

This establishes that

Another way to prove this is by following the definition

of

9.8.1.5. Absolute Value#

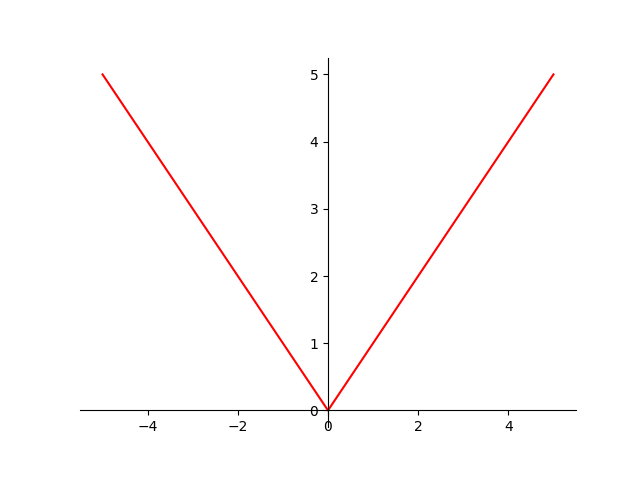

Example 9.28 (Absolute value is convex)

Let

with

Recall that

In particular, for any

Thus

Hence,

9.8.1.6. Norms#

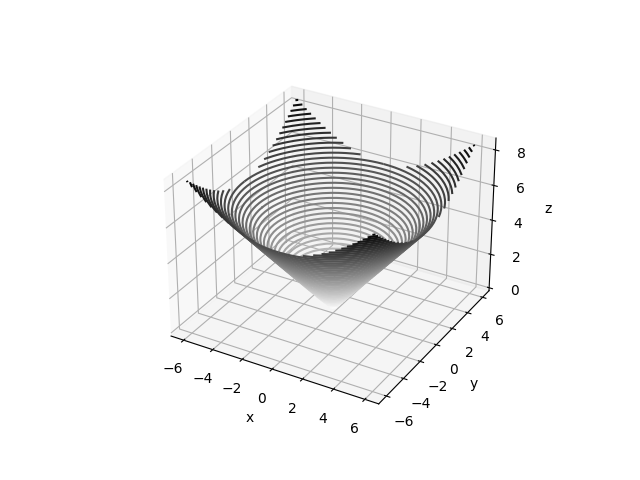

Theorem 9.69 (All norms are convex)

Let

In particular, for any

Thus

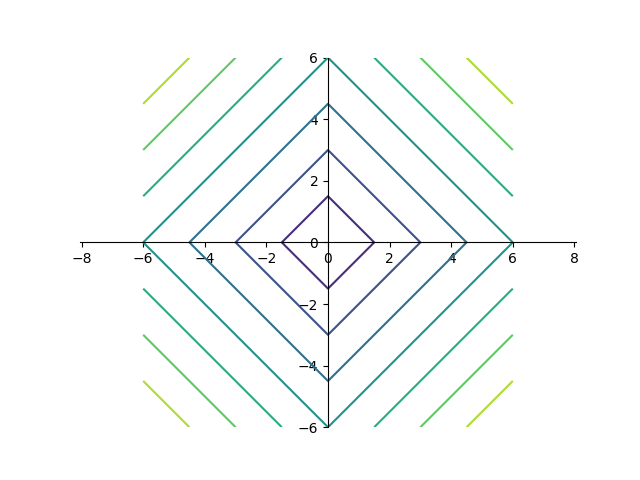

Fig. 9.4

Fig. 9.5

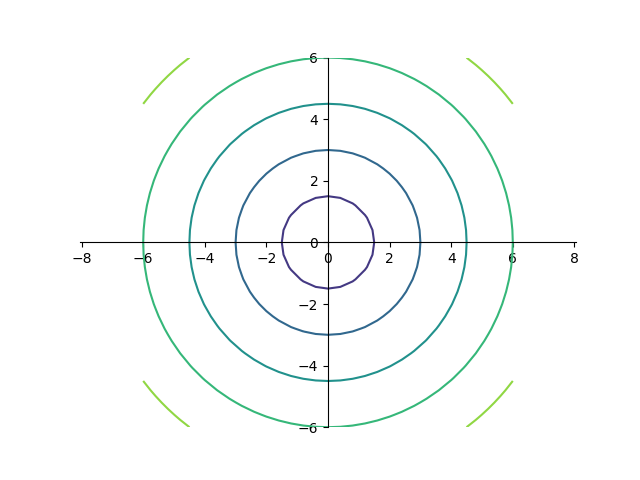

Fig. 9.6

Fig. 9.7

9.8.1.7. Max Function#

Example 9.29 (Max function is convex)

Let

with

Let

Let

Then, for every

Thus,

Taking maximum on the left hand side, we obtain:

But

Thus,

Thus,

9.8.1.8. Geometric Mean#

Example 9.30 (Geometric mean is concave)

Let

with

Recall from AM-GM inequality:

Let

Let

Note that

With

With

Multiplying the first inequality by

Recall that

Thus,

9.8.1.9. Powers#

Example 9.31 (Powers of absolute value)

Let

with

For

Consider the case where

Let

By triangle inequality:

We can write this as:

By Hölder's inequality, for some

Let

Applying Hölder’s inequality,

Taking power of

Which is the same as

Thus,

9.8.1.10. Empty Function#

Observation 9.4 (Empty function is convex)

Let

Proof. The empty set

This observation may sound uninteresting however

it is important in the algebra of convex functions.

Definition 2.48 provides

definitions for sum of two partial functions

and scalar multiplication with a partial

function. If two convex functions

Jensen's inequality, discussed later in the section, generalizes the notion of convexity of a function to arbitrary convex combinations of points in its domain.

9.8.2. Convexity on Lines in Domain#

Theorem 9.70 (

Let

In other words,

Proof. For any arbitrary

we have defined

with the domain:

Assume

Let

It means that there are

and

Let

Note that:

Since

Thus,

We have shown that if

Thus,

Now,

We showed that for any

Thus,

For the converse, we need to show that

if for any

Assume for contradiction that

We show that both of these conditions lead to contradictions.

Assume

Then, there exists

Let

Note that

Picking

Since

This contradicts the fact that

Thus,

We now accept that

Again, let

Pick

We have

In particular,

Since

We have a contradiction.

Thus,

A good application of this result is in showing the concavity of the log determinant function in Example 9.49 below.

9.8.3. Epigraph#

The epigraph

of a function

Fig. 9.8 Epigraph of the function

The definition of epigraph also applies for extended

real valued functions

9.8.3.1. Convex Functions#

Theorem 9.71 (Function convexity = Epigraph convexity)

Let

This statement is also valid for extended real valued functions.

Proof. Let

Assume

Let

Then,

Let

Consider the point

We have

And

Then,

Since

But then,

Thus,

Thus,

Thus,

Assume

Let

Let

Then,

Let

Let

Since

i.e.,

Thus,

Thus,

And,

But

Thus,

Thus,

Note that

Theorem 9.72 (Convex function from convex set by minimization)

Let

Then

Proof. We show the convexity of

Let

Then

By the definition of

Similarly, for every

Consider the sequences

By the convexity of

Hence for every

Taking the limit

Hence

Hence

Hence

9.8.3.2. Nonnegative Homogeneous Functions#

Recall that a real valued function

Theorem 9.73 (Nonnegative homogeneity = Epigraph is cone)

A function

Proof. Let

Let

Let

Then,

But

Thus,

Thus,

Assume

Let

Then,

Since

Now, let

Since

Then,

By definition of epigraph,

We claim that

Assume for contradiction that

Then,

Since

But then,

Hence,

9.8.3.3. Nonnegative Homogeneous Convex Functions#

Theorem 9.74 (Nonnegative homogeneous convex function epigraph characterization)

Let

Proof. By Theorem 9.73,

By Theorem 9.71,

Thus,

Theorem 9.75 (Nonnegative homogeneous convex function is subadditive)

Let

Proof. Assume that

By Theorem 9.74,

Then, by Theorem 9.47

Pick any

Then

Then, their sum

This means that

Now for the converse, assume that

By Theorem 9.73,

Consequently, it is closed under nonnegative scalar multiplication.

Pick any

Let

Then,

Now,

Since

Thus,

We have shown that for any

Thus,

Since

But then, by Theorem 9.74,

Corollary 9.5

Let

Proof. Since

Thus,

But,

Thus,

Thus,

Theorem 9.76 (Linearity of nonnegative homogeneous functions)

Let

If

Proof. We are given that

Assume that

Now, for the converse, assume that

Let

Then,

Also,

But

Thus,

Combining, we get

For any

Thus, for any

Thus,

Since

Finally, assume that

By previous argument

Let

Then,

Since

This can hold only if all the inequalities are equalities in the previous derivation.

Thus,

Then, following the previous argument,

9.8.4. Extended Value Extensions#

Tracking domains of convex functions is difficult.

It is often convenient to extend a convex function

Definition 9.46 (Extended value extension)

The extended value extension

of a convex function

We mention that the defining inequality (9.1)

for a convex function

At

Since

The inequality then reduces to (9.1).

If either

Definition 9.47 (Effective domain)

The effective domain

of an extended valued function

An equivalent way to define the effective domain is:

Theorem 9.77 (Effective domain and sum of functions)

If

Proof. We proceed as follows:

At any

Thus,

Hence,

At any

Thus,

Thus,

Several commonly used convex functions have vastly different domains. If we work with these functions directly, then we have to constantly worry about identifying the domain and manipulating the domain as per the requirements of the operations we are considering. This quickly becomes tedious.

An alternative approach is to work with the

extended value extensions of all functions.

We don’t have to worry about tracking the function

domain. The domain can be identified whenever needed

by removing the parts from

In this book, unless otherwise specified, we shall assume that the functions are being treated as their extended value extensions.

9.8.5. Proper Functions#

Definition 9.48 (Proper function)

An extended real-valued function

In other words,

Putting another way, a proper function

is obtained by taking a real valued function

It is easy to see that the codomain for a proper

function can be changed from

Definition 9.49 (Improper function)

An extended real-valued function

For an improper function

Most of our study is focused on proper functions. However, improper functions sometimes do arise naturally in convex analysis.

Example 9.32 (An improper function)

Consider a function

Then,

9.8.6. Indicator Functions#

Definition 9.50 (Indicator function)

Let

The extended value extension of an indicator function is given by:

Theorem 9.78 (Indicator functions and convexity)

An indicator function is convex if and only if its domain is a convex set.

Proof. Let

since

Thus,

If

Theorem 9.79 (Restricting the domain of a function)

Let

Also,

The statement is obvious. And quite powerful.

The problem of minimizing a function

9.8.7. Sublevel Sets#

Recall from Definition 2.53

that the

The strict sublevel sets for a real valued function

The sublevel sets can be shown to be intersection of a set of strict sublevel sets.

Theorem 9.80 (Sublevel set as intersection)

Let

denote the strict sublevel set of

denote the sublevel set of

Proof. We show that

Let

Then,

Thus,

Thus,

Thus,

We now show that

Let

Then,

Taking the infimum on the R.H.S. over the set

Thus,

Thus,

Theorem 9.81 (Convexity of sublevel sets)

If

are convex.

Proof. Assume

Let

Then,

Let

Let

Since

Thus,

Thus,

Thus,

The converse is not true. A function need not be convex even if all its sublevel sets are convex.

Example 9.33

Consider the function

Its sublevel sets are convex as they are intervals.

Theorem 9.82 (Convexity of strict sublevel sets)

If

are convex.

Proof. Assume

Let

Then,

Let

Let

Since

Thus,

Thus,

Thus,

An alternate proof for showing the convexity of the sublevel sets is to show it as an intersection of strict sublevel sets.

Theorem 9.83 (Intersection of sublevel sets of convex functions)

Let

is a convex set.

Proof. For each

Then,

Thus,

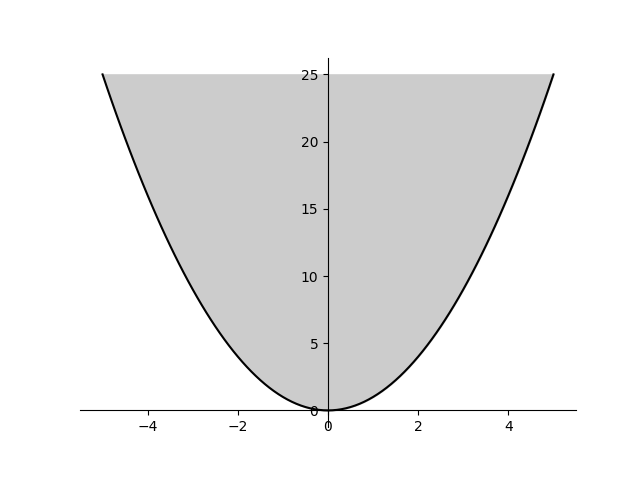

Example 9.34 (Convexity of sublevel sets of the quadratic)

Let

Consider the sets of the form

This is a sublevel set of the quadratic function

Since

Sets of this form include the solid ellipsoids, paraboloids as well as spherical balls. Here is an example of the spherical ball of the norm induced by the inner product.

9.8.8. Hypograph#

The hypograph

of a function

Just like function convexity is connected to epigraph convexity, similarly function concavity is connected to hypograph convexity.

Theorem 9.84 (Function concavity = Hypograph convexity)

A function

Proof.

9.8.9. Super-level Sets#

Recall from Definition 2.56

that the

Theorem 9.85

If

Proof. Assume

Let

Then,

Let

Let

Since

Thus,

Thus,

Thus,

The converse is not true. A function need not be concave even if all its super-level sets are convex.

Example 9.35

Let geometric mean be given by:

with

Let arithmetic mean be given by:

Consider the set:

In Example 9.30 we establish that

In Example 9.26 we established that

Thus,

Thus,

Note that

Thus,

Since

9.8.10. Closed Convex Functions#

Recall from Real Valued Functions that a function is closed if all its sublevel sets are closed. A function is closed if and only if its epigraph is closed. A function is closed if and only if it is lower semicontinuous.

In general, if a function is continuous, then it is lower semicontinuous and hence it is closed.

In this subsection, we provide examples of convex functions which are closed.

9.8.10.1. Affine Functions#

Theorem 9.86 (Affine functions are closed)

Let

where

Proof. We prove closedness by showing that the epigraph of

Let

Let

We have

In other words

Taking the limit on both sides, we get

Hence

Hence

Hence

9.8.10.2. Norms#

Theorem 9.87 (All Norms are closed)

Let

Proof. The sublevel sets are given by

9.8.11. Support Functions#

Definition 9.51 (Support function for a set)

Let

Since

Example 9.36 (Finite sets)

Let

This follows directly from the definition.

9.8.11.1. Convexity#

Theorem 9.88 (Convexity of support function)

Let

Proof. Fix a

is a pointwise supremum of convex functions.

By Theorem 9.114,

We note that the convexity of the support function

9.8.11.2. Closedness#

Theorem 9.89 (Closedness of support function)

Let

Proof. Recall that a function is closed if all its sublevel sets are closed.

Let

Consider the sublevel set

Then,

Thus,

Define

Then,

Now,

Thus,

Thus,

Thus, all sublevel sets of

Thus,

9.8.11.3. Equality of Underlying Sets#

Theorem 9.90 (Equality of underlying sets for support functions)

Let

Proof. If

For contradiction, assume that

Without loss of generality, assume that there exists

Since

Thus, there exists

Taking supremum over

Thus, there exists

This contradicts our hypothesis that

Thus,

9.8.11.4. Closure and Convex Hull#

The next result shows that support function

for a set and its closure or its convex hull

are identical. This is why, we required

Theorem 9.91 (Support functions and closure or convex hull of underlying set)

Let

Proof. We first consider the case of closure.

Thus,

Let us now show the reverse inequality.

Let

Then, there exists a sequence

Now for every

Thus,

Since

Taking the limit

Thus,

Since this is true for every

Now, consider the case of convex hull.

By definition,

Thus,

Let

Then, there exists a sequence

Since

By linearity of the inner product

Taking the limit

Thus,

Since this is true for every

9.8.11.5. Arithmetic Properties#

Following properties of support functions are useful in several applications.

Theorem 9.92 (Arithmetic properties of support functions)

(Nonnegative homogeneity) For any nonempty set

(Subadditivity) For any nonempty set

(Nonnegative scaling of the underlying set) For any nonempty set

(Additivity over Minkowski sum of sets) For any two nonempty subsets

Proof. (1) Nonnegative homogeneity

Here, we used the fact that

(2) Subadditivity

(3) Nonnegative scaling of the underlying set

(4) Minkowski sum

9.8.11.6. Cones#

Recall from Definition 9.22 that a set

Theorem 9.93 (Support function of a cone)

Let

In words, the support function of a cone

Proof. We proceed as follows

Assume that

Then,

In particular,

Accordingly,

Thus,

Now consider

Then, there exists

Since

Accordingly,

Taking the limit

Thus,

Thus,

Example 9.37 (Support function of nonnegative orthant)

Let

which is the nonpositive orthant

9.8.11.7. Affine Sets#

Theorem 9.94 (Support function for an affine set)

Let

Assume that

Proof. We proceed as follows.

By definition of support function

Introduce a variable

Then

Accordingly

where

We note that the statement

In other words,

The set

By Theorem 9.93, the support function of a cone is the indicator function of its polar cone.

By Theorem 9.66, the polar cone is given by

It is easy to see that

Every vector

Accordingly

This gives us

9.8.11.8. Norm Balls#

Theorem 9.95 (Support functions for unit balls)

Let

Then, the support function is given by

where

Proof. This flows directly from the definitions of support function and dual norm.

9.8.12. Gauge Functions#

Definition 9.52 (Gauge function for a set)

Let

If

The gauge function is also known as Minkowski functional.

Property 9.33 (Nonnegativity)

The Gauge function is always nonnegative.

Property 9.34 (Value at origin)

Property 9.35 (Subadditive)

If

Proof. We proceed as follows.

If

Then, the sets

Thus, we can choose some

If

and the inequality is satisfied.

Now, consider the case where

Then,

Now,

Thus,

Since

Thus,

Thus,

Thus, for every

Taking infimum on the R.H.S. over

Property 9.36 (Homogeneous)

The Gauge function is homogeneous.

Property 9.37 (Seminorm)

The Gauge function is a seminorm.

Example 9.38 (Norm as a gauge function)

Let

Let

Then,

The gauge function for the closed unit ball is simply the norm itself.

9.8.13. Jensen’s Inequality#

Jensen’s inequality stated below is another formulation for convex functions.

Theorem 9.96 (Jensen’s inequality)

A proper function

holds true for every

Proof. The Jensen’s inequality reduces to (9.1)

for

Assume

Let

If any of

Thus, we shall assume that

Since

Inductively, assume that the Jensen’s inequality holds for

holds true whenever

WLOG, assume that

Define

Note that

We can now write:

Thus,

For the converse, assume that

Thus,

Jensen’s inequality is essential in proving a number of famous inequalities.

Example 9.39 (Logarithm and Jensen’s inequality)

In Example 9.45, we show that

Now, let

Multiplying by

For a particular choice of

which is the AM-GM inequality suggesting that arithmetic mean is greater than or equal to the geometric mean for a group of positive real numbers.

Theorem 9.97 (Jensen’s inequality for nonnegative homogeneous convex functions)

If

holds true for every

Proof. Let

By Theorem 9.75,

The nonnegative homogeneity gives us

We are done.

9.8.14. Quasi-Convex Functions#

Definition 9.53 (Quasi convex function)

Let

If the sublevel sets